Musical Mondays No. 4

Musical Mondays, produced by a musician for people who are always on the go.

September 4th, 2023

Greetings Victorians!

Welcome to Musical Mondays, where I, Somiah Nettles

, introduce you to a different classical composer on the first Monday of each month in an effort to, in the words of the Berkeley Piano Club, "cultivate and encourage the study, understanding, and appreciation of great music." Because we’ll be honoring one composer for a whole month, on the following Mondays, additional highlights from their lives and music will be made available via Notes.This month, I'd like to introduce you to Florence Beatrice Price, the first African American woman classical composer, pianist, organist of notable reputation, and music teacher, who was born on April 9th, 1887, in Little Rock, Arkansas. Price was the daughter of dentist Dr. James H. Smith and pianist, singer, and businesswoman Florence Irene Smith.

Price began studying piano as a toddler under the tutelage of her mother. At the age of 4, she gave her first piano recital and had her first composition published when she was eleven! Price's mother encouraged her gifted daughter's musical studies, and after graduating as valedictorian from high school at the age of 14, Price went on to study piano and organ at the New England Conservatory of Music, where she began writing her renowned Symphony in E minor. In 1906, at the age of 19, she earned a Bachelor of Music degree, following her mother's advice to present herself as being of Mexican descent. Price was the only one of 2,000 students to pursue a double major (organ and piano performance), and she studied with Frederick S. Converse (piano), George Whitefield Chadwick (music theory), and Henry M. Dunham (organ). Around this time, Price started to think seriously about composing.

Following graduation, she taught music for one year at the Cotton Plant-Arkadelphia Presbyterian Academy in northeastern Arkansas, then at Little Rock’s Shorter College, and from 1910 to 1912 at Clark University in Atlanta. During this time in 1912, she married prominent Arkansas lawyer, Thomas J. Price, and they moved back to her hometown of Little Rock, Arkansas, where she continued to teach privately and became heavily involved in composing until racial unrest in the city broke out due to Jim Crow Laws and a lynching took place near Thomas's office. The family moved to Chicago in 1927, and throughout this period, Florence continued studying composition. In 1928, she published four compositions for piano.

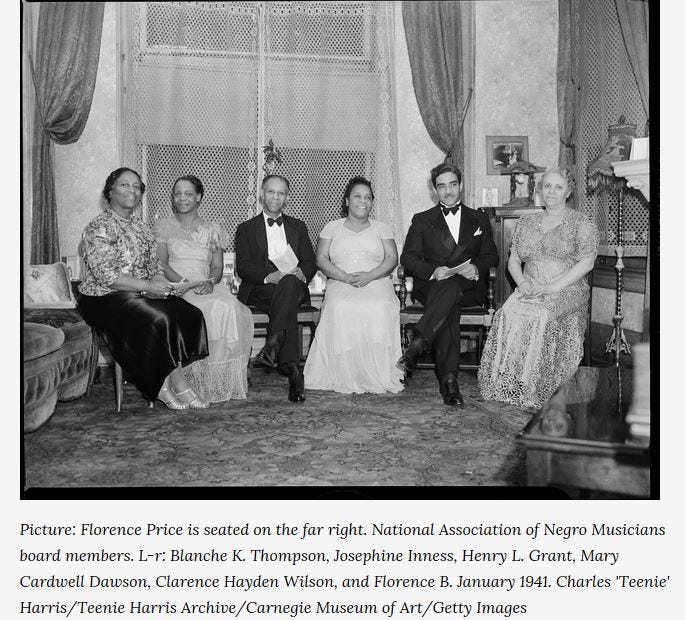

Florence Price was the first African American composer to be represented through the Illinois Federation of Music Clubs. She was a founding member of the National Association of Negro Musicians, of which the Chicago Music Association was the first branch, in the early 1900s. Price was also the first African American member of both the Chicago Club of Women Organists and the Musicians Club of Women. These clubs supported women who were fighting for acceptance in traditionally male-dominated professions like music composition. Colorism played a role in Price’s success. Because of her lighter skin, she was allowed inside these establishments. Unfortunately, and predictably, race and gender discrimination in the realm of composition still hampered her opportunities.

Price and her husband divorced in 1931, leaving her with two daughters to care for. To make ends meet, she began working as an organist for silent cinema screenings and composing songs for radio ads. In 1932, she and her housemate, fellow composer Margaret Bonds, entered the Wanamaker Foundation Awards. Price won first prize for her Symphony in E minor (Bonds won first place in the song category), and on June 15th, 1933, it was performed by the Chicago Symphony Orchestra, making her the first African American woman to have her work performed by a major American orchestra. That night, George Gershwin (American composer and pianist) himself was in the audience. The Chicago Daily News declared Price’s Symphony “a faultless work, a work that speaks its own message with restraint and yet with passion… worthy of a place in the regular symphonic repertoire.”

‘‘[Price] was a deeply religious person, so she brought the music of the African American church into her music, [as well as African-inspired rhythms such as the juba dance], [and] influences from the likes of Dvořák, Tchaikovsky, and other European Romantic composers. Her Symphony in E minor is a thrilling four-movement work packed with soaring melodies, inventive writing (a second movement almost entirely for the brass section!) and gorgeous harmonies’’ (Classic FM). Classic FM: The inspirational life of composer Florence Price

Here it is in its entirety, performed by the Chineke Orchestra, led by Roderick Cox, which I encourage you to listen to while finishing this article. I've also included a link to her Piano Concerto in One Movement, which was performed by the Texas Medical Center Orchestra, led by Libi Lebel.

Price's Symphony in E minor (1931), as well as her Piano Concerto in One Movement (1934) and her String Quartet No. 2 in A minor, II. Andante Cantabilie (1935), are all favorites of mine! Her String Quartet No. 2 in A minor, II. Andante Cantabilie, is dreamlike and ethereal, yet there’s this sense of agony and yearning being exhaled, which is brilliantly brought out by the string instruments. When I listen to Price's Piano Concerto in One Movement, I immediately think of Dvorak's (Czech composer and pianist) New World Symphony. Price's Piano Concerto in One Movement has a romantic ambiance that is tentative, gloomy, and jumpy, with a repeated melody all throughout. In my perspective, this composition sounds like a voyage of self-discovery, replete with ups and downs.

The Andantino movement of Price's Piano Concerto in One Movement opens with trumpets, trombones, and French horns that each appear to be asking a question but only receive an echo, which are the flutes in response, followed by this sense of disquiet brought on by the piano's panging, yearning, dark tones. In the following movement, Adagio, the piano, brass instruments, wind instruments, and string instruments all play in unison to create magnificent enchantment. I appreciate Price’s use of brass instruments because they have such a powerful ability to convey both anguish and beauty so eloquently. The final movement, Andantino, is quite different from the first two. It’s upbeat, joyful, and ends triumphantly.

Price continued to compose a variety of vocal and instrumental ensembles during the 1940s and into the 1950s. She suffered a stroke while preparing to travel to Europe in the summer of 1953. As a result, Florence Beatrice Price died on June 3, 1953.

‘‘Much of Price’s compositional output was considered to be lost until an estimated 200 manuscripts and other papers by the composer were discovered in her former summer house in St. Anne, a suburb of Chicago, in 2009. The discovery offered the musical world a new opportunity to discover Price’s music, perhaps now at a time when her output can be evaluated and appreciated in its own right’’ (Afro Voices). Afrocentric Voices in Classical Music: Florence Price Biography

She composed more than 300 works in her lifetime, varying from small pieces for piano to large-scale compositions such as symphonies and concertos, as well as instrumental chamber music, vocal compositions, and music for radio ads!

That’s all for now, Victorians. I hope you fell in love with Ms. Florence Price's enchanting musicianship like I have, or at the very least learned something new! I'd love to hear your thoughts in the comments section below. Thank you for reading, and remember to subscribe so you never miss a beat.

PS, make sure to check Notes every Monday so you don’t miss out on any additional pieces on Florence Price! Stayed tuned.

Musical Mondays, produced by a musician for people who are always on the go, is brought to you by

.

The "piano" piece was a concerto and I'm listening to it now! Such a dramatic flair she had in her compositions, real emotion.

That symphony was lovely. Looking forward to the piano piece.